Abstract

We combine the publicly available GRACE monthly gravity field time series to produce gravity fields with reduced systematic errors. We first compare the monthly gravity fields in the spatial domain in terms of signal and noise. Then, we combine the individual gravity fields with comparable signal content, but diverse noise characteristics. We test five different weighting schemes: equal weights, non-iterative coefficient-wise, order-wise, or field-wise weights, and iterative field-wise weights applying variance component estimation (VCE). The combined solutions are evaluated in terms of signal and noise in the spectral and spatial domains. Compared to the individual contributions, they in general show lower noise. In case the noise characteristics of the individual solutions differ significantly, the weighted means are less noisy, compared to the arithmetic mean: The non-seasonal variability over the oceans is reduced by up to 7.7% and the root mean square (RMS) of the residuals of mass change estimates within Antarctic drainage basins is reduced by 18.1% on average. The field-wise weighting schemes in general show better performance, compared to the order- or coefficient-wise weighting schemes. The combination of the full set of considered time series results in lower noise levels, compared to the combination of a subset consisting of the official GRACE Science Data System gravity fields only: The RMS of coefficient-wise anomalies is smaller by up to 22.4% and the non-seasonal variability over the oceans by 25.4%. This study was performed in the frame of the European Gravity Service for Improved Emergency Management (EGSIEM; http://www.egsiem.eu) project. The gravity fields provided by the EGSIEM scientific combination service (ftp://ftp.aiub.unibe.ch/EGSIEM/) are combined, based on the weights derived by VCE as described in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)/Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission (Tapley et al. 2004) to map the Earth’s static and time-varying global gravity field has been successfully operated from 2002 till 2017. Using the K-band and GPS measurements from the GRACE twin satellites (Dunn et al. 2003), gravity fields at various spatial scales and temporal resolutions have been derived. They have been used for a wide range of geoscience research such as geodesy, hydrology, oceanography, atmospheric science, and glaciology (e.g., Güntner 2008; Johnson and Chambers 2013; Steffen et al. 2009; and an overview in Wouters et al. 2014).

To acquire dense enough observational coverage to map the Earth’s gravity field up to a spatial resolution of about 400 km, thirty days of measurements are usually required (Tapley et al. 2004) in the standard case of non-repeating orbits. Monthly global gravity fields have been processed and released by the official GRACE Science Data System (SDS, Watkins et al. 2000) which consists of the Center for Space Research at the University of Texas (CSR), the German Research Center for Geosciences (GFZ), and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). There are also additional processing centers, which produce GRACE monthly global gravity fields on a best effort basis such as the Astronomical Institute of the University of Bern (AIUB), the Groupe de recherche de Géodésie spatiale (GRGS), the Technical University of Delft (TU Delft), the Institute of Geodesy at the Graz University of Technology (ITSG), and the Tongji University (Tongji).

From individual processing centers there are up to five consecutive releases of monthly GRACE gravity fields. Different processing strategies were applied, resulting in various noise characteristics of the individual solutions. Numerous studies compare subsets of the available monthly gravity fields in various geophysical applications such as ocean bottom pressure, ice mass change, and glacial isostatic adjustment (e.g., Chambers and Bonin 2012; Johnson and Chambers 2013; Sasgen et al. 2007a; Steffen et al. 2009). Sasgen et al. (2007a) and Sakumura et al. (2014) compared and combined the three official SDS and the GRGS gravity fields.

A combination of the monthly gravity fields reduces the noise of the individual contributions by canceling out systematic errors specific to the different processing strategies. Sasgen et al. (2007a) therefore applied Wiener optimal filtering, minimizing the difference between the linear trends found in the geoid height changes based on the combined solutions and model outputs describing the present-day ice mass change, as well as ongoing glacial isostatic adjustment. The combined solution showed better agreement with the predicted geoid height changes in Antarctica and reduced the non-seasonal variability over the oceans in the spatial domain. Sakumura et al. (2014) compared and combined more recent releases of monthly gravity fields computing the arithmetic mean of the individual contributions and also observed significant noise reduction.

In both combination studies, gravity fields based on variants of the direct approach (Bettadpur and McCullough 2017) were used. However, meanwhile further gravity fields from processing centers that are not members of the official SDS have become available. These additional time series are determined based on various alternative approaches such as the celestial mechanics approach (Beutler et al. 2010a, b), the short arc approach (Mayer-Gürr 2006), and the modified acceleration approach (Liu et al. 2010). The full set of these different gravity field time series has not yet been rigorously compared nor combined. A further drop of noise levels can be expected from this combination.

The combinations achieved by Sasgen et al. (2007a) and Sakumura et al. (2014) were limited to maximum degree and order 50, due to the limited resolution of the GRGS release 1 or 2 contributions. However, GRGS’s release 3 now is available up to degree 80. Moreover, some of the processing centers provide various monthly gravity fields up to degrees 60, 90, or even 120. Combined solutions up to degrees higher than 50 have not yet been investigated. In Sasgen et al. (2007a) and Sakumura et al. (2014), the combined gravity fields were evaluated in the spatial domain only. We gain further insight by investigating the different noise characteristics also in the spectral domain. Based on their reduced set of contributions, Sakumura et al. (2014) could not demonstrate weighting to be beneficial. With the larger set of gravity fields, a proper weighting scheme is expected to improve the combination, especially in case of diverse noise levels of the individual gravity fields.

In this study, we compare the full set of currently available monthly GRACE gravity fields. We combine all time series with comparable signal content, i.e., without obvious regularization. We therefore test five different weighting schemes including the arithmetic mean. Finally, we evaluate the combinations in terms of signal and noise in both the spectral and the spatial domains. The study is performed in the frame of the project European Gravity Service for Improved Emergency Management (EGSIEMFootnote 1) in preparation of a future combination service comparable to the International GNSS Service (IGS; Dow et al. 2009), the International VLBI Service (IVS; Schlüter and Behrend 2007), or the International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS; Pearlman et al. 2002).

2 Database of GRACE monthly gravity fields

We consider all monthly GRACE gravity fields provided by the International Center for Global Earth Models (ICGEMFootnote 2), as listed in Table 1. Figure 1 (top) visualizes the availability of the individual monthly gravity fields. Gaps are related to missing observational data, mainly in the early and late mission phases, and to periods of orbit resonance. The latter can be inferred from the maximum longitudinal spacing of neighboring ground tracks per month, as shown in Fig. 1 (bottom). The density of the ground tracks of the satellites directly determines the achievable spatial and spectral resolution of the derived monthly gravity field (Weigelt et al. 2013; Klokočník et al. 2015). Extended periods of orbit resonances are encountered around September 2004 and May 2012. A period of less pronounced resonances during the years 2009 and 2010 did not impair the monthly gravity fields. Some processing centers that provide high-degree gravity fields during periods with little observation coverage or orbit resonance adopt regularization techniques (e.g., Dahle 2017). Regularized gravity fields were excluded from the combination.

The individual time series listed in Table 1 are preprocessed prior to the comparison and combination. The radius of the Earth \(a_\mathrm{ref}\) is set to a common value of 6378136.3 m and the Earth’s gravitational parameter \(G M_\mathrm{ref}\) to \(3.986004415\times 10^{14}\) m3/s2. Both values are consistent with the IERS Conventions 2010 (Petit and Luzum 2010). When necessary, the individual gravity fields’ fully normalized spherical harmonic coefficients \(\bar{C}_{lm}\) and \(\bar{S}_{lm}\) of degree l and order m are rescaled (Hofmann-Wellenhof and Moritz 2006):

where the subscripts orig and ref indicate the original and reference values.

Each time series of the individual monthly gravity field solutions is screened separately. Outliers are determined on the basis of the RMS of the non-seasonal variability over the oceans, which is a good indicator for the noise level of a gravity field (see Sect. 3.2). As threshold three times the median absolute deviationFootnote 3 is used. Up to five monthly gravity fields per time series, mostly in the early mission phase before 2004 and around the resonance period in May 2012, are excluded by the screening. Finally, we group the individual time series according to their maximum degrees 60, 90, or 120. The degree 80 GRGS gravity fields are cut to degree 60 and the degree 96 CSR gravity fields are cut to degree 90, to be comparable to the other time series.

3 Comparison of individual time series

The preprocessed time series are compared in the spatial domain in terms of signal and noise. This step is necessary to exclude obviously regularized time series that may bias the combination. We study the mean equivalent water height (MEWH) within selected river basins to assess the signal content and the RMS of the non-seasonal variability over the oceans to assess the noise levels of the monthly gravity fields. The \(C_{20}\) coefficient is excluded from the analysis because it is degraded in most of the GRACE gravity fields (Chen et al. 2005) and normally replaced by SLR-derived values (e.g., Chambers and Bonin 2012; King et al. 2012 and Velicogna and Wahr 2013).

3.1 Signal content

We compare the amplitudes of annual variations of MEWH within selected river basins. Therefore, the unitless spherical harmonic coefficients of the individual gravity fields are transformed to equivalent water heights (EWH, Wahr et al. 1998) and the \(3^{\circ }\times 3^{\circ }\) grids on the Earth’s surface are synthesized. The grid cells are weighted by the sine of their colatitude. The MEWH within a river basin is computed as the normalized sum over all basin grid cells (e.g., Eq. (8) in Zhao et al. 2011). For this signal evaluation, all gravity fields were truncated at degree 60 and no filtering was applied.

In Fig. 2, the MEWH of Amazon, Ganges, and Mekong river basins are shown. A strong seasonal variation is visible in all three examples. In most of the time series, the amplitude of these variations is comparable. However, the DMT time series has attenuated signal because it is already pre-filtered during the data processing (Liu et al. 2010). In many river basins, the annual amplitude of MEWH derived from DMT violates a threshold of three times the median absolute deviation, considering all time series. Hence, the DMT solution is not included in the combination in this study.

3.2 Noise level

We compare the individual time series in terms of noise using the RMS of anomalies over the oceans, again weighted by the sine of the colatitude of the grid cells (Meyer et al. 2015). Anomalies characterize the non-seasonal variability and are defined as the residuals after subtraction of a best fitting bias, trend, annual and semiannual variations from the EWH of each grid cell. In Fig. 3, the RMS of anomalies per grid cell of the AIUB 02 (60) time series from 2003 to 2011, smoothed using a 300-km Gauss filter, is shown. Over the oceans, very little variation is visible, while over the continents strong signals related to hydrology are observed. To avoid leakage from continental signal into the oceans, we shrink the oceans by two grid cells, i.e., by \(6^\circ \) along all coasts, then computed the weighted RMS of anomalies over all ocean grid cells according to

where \(N_\mathrm{grid}\) is the number of grid cells in the selected ocean areas, \(\varTheta _i\) and \(\lambda _i\) are the colatitude and longitude at the center points of the grid cells i, and \(e_i\) is the corresponding EWH anomaly at time t.

Figure 4 shows the monthly weighted RMS over the oceans for the individual degree 60 and 90 gravity fields, without (left) or with smoothing (right) by a 300-km Gaussian filter which reduces noise, especially in the high-degree coefficients (Jekeli 1981; Wahr et al. 1998). The GRGS time series exhibits a distinctly low noise level and also the least fluctuations. This is due to a regularization during the data processing (Lemoine et al. 2013). Consequently, the GRGS time series was not considered for combination. The other contributions have comparable noise levels and show similar fluctuations, such as increased noise around periods of orbit resonance. Neglecting the GRGS gravity fields, the ITSG time series has the lowest noise levels in both the degree 60 and the degree 90 cases. This is most probably due to the empirical noise modeling applied in their approach (Mayer-Gürr et al. 2014).

4 Combination of gravity fields

In this section, we combine all gravity fields that passed the quality control, testing five weighting schemes. Combinations are separately performed for the degree 60 and 90 gravity fields. Combination is achieved by a weighted averaging scheme

where \(w_{l,m}^{i,t}\) is the weight applied to coefficient X (either C or S) of degree l and order m, in gravity field i at time t. \(N_\mathrm{sol}\) is the number of contributions. The formal error of the weighted mean is

The weights are derived by pairwise comparison of the individual contributions to the arithmetic mean in case of the non-iterative weighting schemes and by variance component estimation in case of iteration. For the degree 60 combination, the following time series are considered: AIUB 02 (60), CSR 05 (60), ITSG2014(60), and Tongji 01 (60). Degree 60 combinations are performed for the period March 2003 to August 2011. For the degree 90 solutions we consider AIUB 02 (90), CSR 05 (96) truncated at degree 90, GFZ 5a (90), ITSG2014(90), and JPL 05 (90). The degree 90 combination is performed for the period March 2003 to March 2014. Whenever gravity fields are missing or screened out in one of the contributing time series, no combined solution is generated for that month. \(C_{20}\) is excluded from the combination and the derivation of weights.

4.1 Arithmetic mean

The arithmetic mean is the simplest way to compute combined solutions. Each gravity field coefficient enters the combination with equal weight.

4.2 Coefficient-wise weighting

Weights are computed per gravity field coefficient by the inverse of the squared difference to the arithmetic mean (Table 2). This weighting scheme corresponds to the inverse of the squared variance which is commonly used in statistics. Figure 5 shows the normalized coefficient-wise weights per time series (averaged over all monthly combinations for this illustration). AIUB, CSR, and ITSG in general obtain higher weights than GFZ, JPL, and Tongji. The AIUB contribution obtains the highest weights, indicating that the AIUB gravity fields are closest to the arithmetic mean, i.e., are least affected by biases. However, its coefficients at resonance orders (15, 31, 46, 61, 76) seem to be deteriorated. The CSR gravity fields obtain high weights at their high-degree low-order coefficients. This corresponds to the observation that their noise level in the corresponding spectral range is very low.

The ITSG gravity fields also in general obtain high weights at low orders, with the exception of the zonal terms and degree 3 coefficients. The ITSG zonal coefficients are systematically different from the other contributions due to ITSG’s use of satellite attitude data that were generated by sensor fusion of star cameras and angular rotations recorded by the onboard accelerometers (Klinger and Mayer-Gürr 2015). This change mainly affects the geometric K-Band correction. Its effect on the zonal coefficients could be reproduced at AIUB for the test month January 2007, replacing the original GRACE Level 1B data with ITSG’s sensor fusion data (Fig. 6, left). Note that, compared to the general noise levels of the gravity fields (see Fig. 11), the effect of the sensor fusion data on the zonal coefficients is quite small, but systematic.

The main difference between the original L1B and the sensor fusion data is a significant reduction in high-frequency noise. We therefore made one additional test and simply smoothed the original geometric K-band correction using a low-pass Savitzky–Golay filter (Savitzky and Golay 1964) of polynomial order 3 and a half window length of 60 seconds. The effect on the zonal coefficients (Fig. 6, right) closely resembles the true sensor fusion results. We conclude that by smoothing the geometric K-band correction the zonal coefficients can be improved. This example reveals a weakness of all weighting schemes based on comparison to a mean: A superior contribution cannot be distinguished from a degraded one if it systematically differs from the bulk of contributions.

The Tongji time series in contrast to AIUB, CSR, and ITSG obtains lower weights at low orders. JPL has problems at resonance orders, but profits for sectorial coefficients. GFZ in contrary obtains rather high weights around resonance orders in response to the degradation at these orders in the AIUB and JPL contributions.

4.3 Order-wise weighting

Spherical harmonic coefficients of the same order and parity are correlated, as it becomes evident applying the concept of lumped coefficients (Sneeuw 1992). This correlation results in comparable noise characteristics per order and motivated an order-wise weighting scheme, drastically reducing the number of weights. The order-wise weights can be derived from the coefficient-wise differences according to Table 2.

The order-wise weights per gravity field are shown in Fig. 7 for the whole period. As expected from the previous results, AIUB, CSR, and ITSG again obtain generally higher weights. In case of the Tongji time series, it becomes obvious that the low weights at low orders are mainly caused by a degradation at these orders toward the end of the period. GFZ correspondingly shows degraded performance before 2006 and from 2012 to 2014. This agrees well with periods of increased noise as shown in Fig. 4 and corresponds to periods of increased solar and correspondingly ionosphere activity.

In Fig. 8, the order-wise weights are averaged over the whole time span, showing their relative levels. These relative levels are maintained for most orders except around resonances. At resonance orders, most gravity fields seem to have common problems, increasing the noise levels and leading to a harmonization of the individual weights. This phenomenon can be explained by aliasing of unmodeled long-periodic signals of geophysical origin into resonant orders (Seo et al. 2008).

4.4 Field-wise weighting

The number of weights is further reduced by field-wise weights. These again can be derived from the coefficient-wise differences as detailed in Table 2. In Fig. 9, the time series of the field-wise weights are shown. Again, AIUB, CSR, and ITSG get the highest weights. From April 2011 on, when the active thermal control of the GRACE satellites was switched off in order to preserve the decaying batteries, ITSG2014 performs best. This change in the instruments’ environment had an impact on the performance of the accelerometers (Klinger and Mayer-Gürr 2016). The empirical noise modeling strategy at ITSG obviously is best able to cope with the resulting change in the accelerometer noise characteristics.

4.5 Iteration by variance component estimation

Finally, we introduce iteration by VCE (e.g., Kusche 2003; Teunissen and Amiri-Simkooei 2008 for geodetic applications), because the arithmetic mean as reference can easily be biased. VCE is usually applied on normal equation level, but here we want to use it for the combination on solution level. We therefore rewrite the combination in terms of a least-squares process with observation equations

where \(\varvec{A}_i\) is the design matrix, \(\varvec{x}_i\) the vector of unknown gravity field coefficients, \(\varvec{l}_i\) the vector of observed gravity field coefficients, \(\epsilon _i\) the noise, \(i=1,2,\ldots ,N_\mathrm{sol}\) the index of the gravity field, and \(N_\mathrm{sol}\) the number of gravity fields to be combined. We deal with the most simple case, where the gravity field coefficients are directly observed and \(\varvec{A}_i\) is equal to the identity matrix. In this case, the noise term vanishes completely and the solution

with normal equations \(\varvec{N}_i=\varvec{A}_i^T\varvec{A}_i\) and right-hand side vectors \(\varvec{b}_i=\varvec{A}_i^T\varvec{l}_i\) reduces to \(\hat{\varvec{x}}_i=\varvec{l}_i\).

Now, we perform a weighted combination

where the weights \(\hat{w}_i\) are derived iteratively following the formalism of VCE:

with residuals

and partial redundancies

where (k) indicates the iteration depth.

Convergence in our case is fast, normally after 3–5 iterations. The field-wise weights derived by VCE are shown in Fig. 10. By the iteration, the weights tend to be intensified in the sense that high weights get even higher and low weights even lower. The relative order of the different contributions is not changed.

5 Evaluation of the combined solutions

We evaluate the combined solutions in both the spectral and the spatial domains. We focus on the noise assessment because the signal content of the combined solutions is expected to be similar to that of the individual contributions. In the spectral domain, we evaluate the combined solutions, investigating the RMS and the degree amplitudes of the coefficient-wise anomalies. Additionally, we examine the significance of annual variations per coefficient applying a statistical F-test. In the spatial domain, we use the weighted RMS of anomalies over the oceans to assess the noise. We also estimate secular mass change in Antarctica and compare the size of the RMS of residuals.

5.1 Spectral domain

5.1.1 Coefficient-wise anomalies

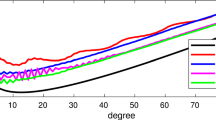

The coefficient-wise anomalies are defined as the residuals after subtraction of deterministic models consisting of bias, trend, annual, and semiannual variations from the time series of spherical harmonic coefficients (compare to Sect. 3.2). Figure 11 shows the coefficient-wise RMS of anomalies of the individual contributions and of the combined solutions of the degree 60 (top) or 90 (bottom) gravity fields. We focus on the comparison of the simple arithmetic mean and the weighted mean using VCE because they perform best. The coefficient-wise weighting scheme is obviously impaired by the small sample size. It is the same for the order-wise weighting scheme in case of high orders.

In Fig. 11, we can distinguish three different sections of spherical harmonic coefficients: low degrees, high orders, and the central part of the triangles of coefficients. The central part containing the low- to medium-order coefficients generally has smaller anomalies than the corners containing the low-degree or high-order coefficients. The low- to medium-order coefficients usually contain less noise than the high-order coefficients. The relatively large anomalies in the low-degree coefficients are most probably caused by unmodeled signal, whereas the larger anomalies in the high-order coefficients are dominated by colored noise. For the assessment of the noise, we focus on the high-order coefficients. The degree 60 individual contributions are more similar than the degree 90 individual contributions because the latter contain more noisy high-order coefficients.

In both the degree 60 and 90 cases, the combined solutions have smaller coefficient-wise RMS than the individual contributions. This indicates that the coefficients of the combined solutions are less noisy and fit the modeled signals better than the individual contributions. However, the zonal coefficients of the degree 60 and 90 ITSG time series have smaller anomalies than the corresponding combined solutions. This effect is related to the use of the sensor fusion attitude data by ITSG (see Sect. 4.2). The high quality of the ITSG zonal coefficients is not adequately represented by the different weighting schemes and the combination does not profit.

The weighted mean has smaller anomalies than the arithmetic mean in both the degree 60 and 90 cases. As expected, the difference is more pronounced in the degree 90 case: The improvement in the weighted mean with respect to the arithmetic mean is 0.9% in the degree 60 case and 1.6% in the degree 90 case. The diverse degree 90 gravity fields profit more from the weights than the uniform degree 60 gravity fields.

We also generate combinations of subsets of the gravity fields containing only the official SDS time series from CSR, GFZ, and JPL (Fig. 12). Compared to the reduced combinations, the combined solutions including the full set of contributions have definitely smaller anomalies: The improvements are 22.4% in case of the arithmetic mean and 20.1% in case of the weighted mean. This experiment proves that the alternative gravity field time series significantly improve the quality of the combination.

5.1.2 Degree amplitudes of anomalies

The coefficient-wise anomalies may be condensed to degree amplitudes to give a clearer view of the noise characteristics of the spherical harmonic spectrum. Figure 13 shows the medians of the degree amplitudes of the anomalies per time series in the degree 90 case. First, only coefficients up to order 29 are considered to focus on the geophysically most meaningful part of the spectrum (left), then all coefficients are included (right). The motivation for truncation at order 29 is to exclude the noisy coefficients around the second resonant order 31.

The combined solutions have smaller degree amplitudes than the individual contributions up to degree 60. Beyond degree 60, the ITSG contribution performs as good as or even better than the combinations. But small anomalies could also indicate attenuated signal. In a simulation study based on white noise, a comparable behavior could be reproduced including an individual contribution containing attenuated signal (Jean et al. 2016). However, in our case we could not prove any signal attenuation in the ITSG contribution. Moreover, the small anomalies of the ITSG gravity fields are observed at high degrees where the signal content of the anomalies is rather small, compared to the noise. Therefore, we conclude that the ITSG solution contains obviously less noise in the high-degree coefficients than even the combined solutions.

Overall, the different weighting schemes perform similarly. The weighted means outperform the arithmetic mean in the higher degree coefficients approximately beyond degree 60. This is the part of the spectrum where the individual contributions are most diverse and the greatest benefit due to the weighting has to be expected. Among the weighted means, the combination based on VCE excels. Among the non-iterative combinations, the coefficient-wise weighting unexpectedly performs worst. This is most probably caused by the small sample size of only four (in the degree 60 case) or five (in the degree 90 case) time series available for combination.

5.1.3 Significance of annual variations

In addition to the study of anomalies, we perform a statistical F-test to assess the signal content within the different time series of monthly gravity fields. We focus on the annual variations that are mainly caused by the hydrological cycle. To test the significance of the signal under question, we fit deterministic models with or without the corresponding model parameter to time series of the individual gravity field coefficients. The F-test evaluates the ratio of the residuals of the complete and the reduced model (e.g., Davis et al. 2008 or Meyer et al. 2012). Our complete model consists of offset, trend, annual, and semiannual periodic signals.

Figure 14 shows the result of the hypothesis test at the 99% confidence level. Most of the accepted coefficients are concentrated in the low-to-middle degrees at low orders. The number of accepted coefficients in the degree 90 combination based on VCE is larger than in all individual contributions, closely followed by the ITSG contribution. In the degree 60 case, ITSG performs as good as the combination. In principle, the significance test is based on the signal-to-noise ratio of the gravity field coefficients. This explains why in the noisy high-degree coefficients almost no significant annual variation can be detected.

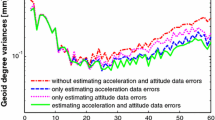

Weighted RMS of anomalies over the oceans in the degree 60 (top) or 90 (bottom) individual and combined monthly gravity fields, either unsmoothed (left) or smoothed by a 300-km Gauss filter (right). The median of the time series of RMS within a common time span is given in the legend for the combinations (The corresponding information for the individual contributions can be found in Fig. 4)

5.2 Spatial domain

5.2.1 Weighted RMS of anomalies over the oceans

In the spatial domain, we first focus on the noise levels as indicated by the RMS of the anomalies over the oceans, weighted by the sine of the colatitude of the grid cells (see Sect. 3.2). As shown by Fig. 15, the combined solutions in general have smaller anomalies over the oceans than the individual contributions, except for the unfiltered degree 90 case where the ITSG contribution sometimes even outperforms the combinations. After smoothing, the combined solutions outperform all individual contributions in both the degree 60 and 90 cases.

The five different weighting schemes result in very similar noise levels. In the degree 60 case, no clear advantage for one of the weighting schemes can be found: The reduction in noise relative to the arithmetic mean is at the level of 1.3% only. In the unsmoothed degree 90 case, order-wise weights or VCE produces the best results: The reduction in noise amounts to 7.7% with respect to the arithmetic mean. This difference is ironed out by smoothing.

We conclude that weighting only is worth the effort in case of degree 90 monthly gravity fields where the noise content in the high-degree and high-order coefficients differs significantly between the individual contributions. This is in line with Sakumura et al. (2014) who truncated all gravity fields at degree 50 prior to combination and concluded that in this case no weights are needed. Moreover, the benefit of weighting becomes obvious in the presence of outliers, as the case in January 2007 in the degree 90 case, where all weighted combinations clearly outperform the arithmetic mean.

Finally, we again compute subset combinations based only on the official SDS time series and compare them to the combinations of the full set of contributions. The subset combinations have significantly larger anomalies (Fig. 16) than the regular combinations. The improvement taking all contributions into account amounts to 25.4% in terms of the median of the weighted RMS of the anomalies over the oceans.

5.2.2 Mass trends in Antarctica

To further assess the signal and noise content in the spatial domain, we compute mass trends in Antarctica. Antarctica is one of the most interesting regions to observe the effects of global climate change. The GRACE gravity field solutions have been used to examine the rapidly decreasing ice mass in Antarctica (Chen et al. 2006; Ramillien et al. 2006; Sasgen et al. 2007b; King et al. 2012; Velicogna and Wahr 2013). The published ice mass trends derived from the GRACE monthly gravity fields are very diverse because they depend on the considered time spans, on the filters applied to reduce the noise, on the measures taken against signal leakage, and on model assumptions for signal separation of global isostatic adjustment and seasonal snow cover (Steffen et al. 2009). Less noisy monthly gravity fields would be of major interest because consequently the applied smoothing and the related signal loss by leakage could be reduced.

We fit deterministic models consisting of bias, trend, annual, and semiannual periodic signal to the time series of MEWH within the 27 major glacial basins of Antarctica (Fig. 17), considering the arithmetic mean, the combination based on VCE, and the individual contributions. The estimated linear trends, estimated for the period from February 2003 to November 2011 from the unfiltered degree 60 or 90 time series, are shown in Fig. 18 (top). To derive residuals representative for the noise (Fig. 18, bottom), we further reduce quadratic trends. We compute the mass in each drainage basin simply from the basins’ MEWH without further corrections. This is justified because the purpose of this investigation is the comparison of the combined solutions with respect to the individual contributions rather than the derivation of ice mass change in Antarctica.

Most of the degree 60 or 90 individual or combined solutions result in similar trend estimate within thresholds of 3 times the median absolute deviations (Fig. 18, top). Only the Tongji and JPL time series show larger deviations. The RMS of the residuals (Fig. 18, bottom) is the lowest for the combinations and the ITSG time series. In the degree 60 case, the combined solutions are least noisy in most of the glacial basins, especially in the small basins in Western Antarctica, numbered from 20 to 22, where the mass loss is most prominent. In the degree 90 case, the ITSG time series is often less noisy than even the combined solutions, as it was also found in the case of anomalies over the oceans in the previous section.

The trend estimates confirm that the signals are well preserved in the combination in both the degree 60 and 90 cases. The arithmetic mean and the weighted mean perform comparably in terms of the RMS of residuals in the degree 60 case, whereas the improvement in the weighted mean over the arithmetic mean is 18.1% on average over the 27 drainage basins in the degree 90 case. Again, we conclude that in case of degree 90 gravity fields it is beneficial to apply weights in the combination.

6 Conclusion

We compared all currently available monthly GRACE gravity field time series in the spectral and the spatial domains. Most of the individual time series contain comparable mass transport signals and noise levels except for the DMT time series that has been pre-filtered in the data processing and the GRGS 03 time series that is regularized. Some of the alternative time series that are not official GRACE SDS products perform very well in terms of signal-to-noise ratio.

We further created combinations of the individual gravity field time series, excluding pre-filtered or regularized gravity fields. Compared to previous studies, the combination is extended to maximum spherical harmonic degree 90 and five different weighting schemes are explored. Degree 60 or 90 gravity fields are studied and combined separately.

For noise assessment in the spectral domain, the coefficient-wise RMS and the degree amplitudes of anomalies are computed. The signal content is evaluated applying a statistical F-test to the annual variation per coefficient. In the spatial domain, the weighted RMS of EWH anomalies over the oceans and mass trend estimates in Antarctica are studied.

All experiments yield consistent results: By combination the noise in general is reduced, while the signal content of the individual contributions is preserved. However, the degree 90 ITSG time series, which was generated applying empirical noise modeling, performs comparably well to the combined solutions.

Subset combination of only the SDS time series leads to significantly increased noise levels: The coefficient-wise RMS of anomalies is increased by up to 22.4%, while the weighted RMS of anomalies over the oceans is increased by 25.4%. In general, the weighted combinations perform better than the arithmetic mean in both the spectral and spatial domains. This is especially true for the unsmoothed degree 90 gravity fields that exhibit rather diverse noise characteristics in their high-degree and order coefficients: The weighted RMS of anomalies over the oceans is reduced by 7.7% in the weighted combination compared to the arithmetic mean, and residuals after trend estimation in Antarctic glacial basins are reduced by 18.1% in average over 27 major glacial basins.

We conclude that well-designed weighting schemes are necessary to produce optimal combined solutions when the individual solutions have diverse noise characteristics. With a small sample size of 4 to 5 time series considered for combination, a field-wise weighting scheme performs better than coefficient- or order-wise weighting schemes. Iteration by VCE was found to be helpful in general.

To further improve the combination results, advanced noise modeling strategies in the individual contributions would be beneficial, as shown by ITSG. With a larger number of time series, coefficient-wise weighting schemes that take into account the noise characteristics of the individual gravity field coefficients are expected to perform better than order- or field-wise weighting schemes. External comparison with hydrological, glaciological, or oceanographic observational data would strengthen the validation, but is beyond the scope of this study.

The GRACE gravity field combinations produced by the EGSIEM project make use of the VCE weighting scheme investigated in this study. They are available at ftp://ftp.aiub.unibe.ch/EGSIEM/.

Notes

A robust measure of dispersion, computed as \(\mathbf median (|X_i-\mathbf median (X)|)\) for variable X where i is the index of each element in X.

References

Bettadpur S (2012) UTCSR Level-2 Processing Standards Document. Tech. rep., Center for Space Research, University of Texas at Austin

Bettadpur S, McCullough C (2017) The classical variational approach. In: Naeimi M, Flury J (eds) Global gravity field modeling from satellite-to-satellite tracking data. Lecture notes in earth system sciences. Springer, Cham, pp 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49941-3_3

Beutler G, Jäggi A, Mervart L, Meyer U (2010a) The celestial mechanics approach: theoretical foundations. J Geod 84(10):605–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-010-0402-6

Beutler G, Jäggi A, Mervart L, Meyer U (2010b) The celestial mechanics approach: application to data of the GRACE mission. J Geod 84(11):661–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-010-0402-6

Chambers DP, Bonin JA (2012) Evaluation of release-05 GRACE time-variable gravity coefficients over the ocean. Ocean Sci 8(5):859–868. https://doi.org/10.5194/os-8-859-2012

Chen JL, Rodell M, Wilson CR, Famiglietti JS (2005) Low degree spherical harmonic influences on gravity recovery and climate experiment (GRACE) water storage estimates. Geophys Res Lett 32:L14405. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL022964

Chen JL, Wilson CR, Blankenship DD, Tapley BD (2006) Antarctic mass rates from GRACE. Geophys Res Lett 33:L11502. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026369

Chen Q, Shen Y, Zhang X, Hsu H, Chen W, Ju X, Lou L (2015) Monthly gravity field models derived from GRACE Level 1B data using a modified short-arc approach. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 120(3):1804–1819. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011470

Dahle C (2017) Release Notes for GFZ GRACE Level-2 Products - version RL05. Tech. rep., GFZ

Dahle C, Flechtner F, Gruber C, König D, König R, Michalak G, Neumayer KH (2012) GFZ GRACE Level-2 Processing Standards Document for Level-2 Product Release 0005. Tech. rep., GFZ, https://doi.org/10.2312/GFZ.b103-12020

Davis JL, Tamisiea ME, Elosegui P, Mitrovica JX, Hill EM (2008) A statistical filtering approach for gravity recovery and climate experiment (GRACE) gravity data. J Geophys Res 113:B04410. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JB005043

Dow JM, Neilan RE, Rizos C (2009) The International GNSS Service in a changing landscape of Global Navigation Satellite Systems. J Geod 83(3):191–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-008-0300-3

Dunn C, Bertiger W, Bar-Sever Y, Desai S, Haines B, Kuang D, Franklin G, Harris I, Kruizinga G, Meehan T, Nandi S, Nguyen D, Rogstad T, Thomas J, Tien J, Romans L, Watkins M, Wu SC, Bettadpur S, Kim J (2003) Instrument of GRACE: GPS augments gravity measurements. GPS World 14(2):16–28

Güntner A (2008) Improvement of global hydrological models using GRACE data. Surv Geophys 29(4):375–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-008-9038-y

Hofmann-Wellenhof B, Moritz H (2006) Physical geodesy. Springer, Wien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-211-33545-1

Jean Y, Meyer U, Jäggi A (2016) Simulation study on combination of GRACE monthly gravity field solutions. In: EGU General Assembly 2016, vol 18, EGU2016-13452

Jekeli C (1981) Alternative methods to smooth the Earth’s gravity field. PhD thesis, Ohio State University

Johnson G, Chambers D (2013) Ocean bottom pressure seasonal cycles and decadal trends from GRACE release-05: Ocean circulation implications. J Geophys Res Oceans 118(9):4228–4240. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20307

King M, Bingham R, Moore P, Whitehouse P, Bentley MJ, Milne G (2012) Lower satellite-gravimetry estimates of Antarctic sea-level contribution. Nature 491:586–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11621

Klinger B, Mayer-Gürr T (2015) Improved GRACE preprocessing methodologies: impact on monthly gravity field solutions. In: EGU General Assembly 2015, vol 17, EGU2015-10739

Klinger B, Mayer-Gürr T (2016) The role of accelerometer data calibration within GRACE gravity field recovery: results from ITSG-Grace2016. Adv Space Res 58(9):1597–1609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2016.08.007

Klokočník J, Wagner C, Kostelecký J, Bezděk A, Novák P, McAdoo D (2008) Variations in the accuracy of gravity recovery due to ground track variability: GRACE, CHAMP, and GOCE. J Geod 82(12):917–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-008-0222-0

Klokočník J, Wagner C, Kostelecký J, Bezděk A (2015) Ground track density considerations on the resolvability of gravity field harmonics in a repeat orbit. Adv Space Res 56(6):1146–1160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2015.06.020

Kusche J (2003) A Monte-Carlo technique for weight estimation in satellite geodesy. J Geod 76(11):641–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-002-0302-5

Lemoine JM, Bruinsma S, Gegout P, Biancale R, Bourgogne S (2013) Release 3 of the GRACE gravity solutions from CNES/GRGS. In: EGU General Assembly 2013, vol 15, EGU2013-11123

Liu X, Ditmar P, Siemes C, Slobbe DC, Revtova E, Klees R, Riva R, Zhao Q (2010) DEOS Mass Transport model (DMT-1) based on GRACE satellite data: methodology and validation. Geophys J Int 181(2):769–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04533.x

Mayer-Gürr T (2006) Gravitationsfeldbestimmung aus der Analyse kurzer Bahnbögen am Beispiel der Satellitenmissionen CHAMP und GRACE. PhD thesis, Institut für Theoretische Geodäsie der Universität Bonn

Mayer-Gürr T, Zehentner N, Klinger B, Kvas A (2014) ITSG-Grace2014: a new GRACE gravity field release computed in Graz. In: GRACE Science Team Meeting (GSTM), https://online.tugraz.at/tug_online/voe_main2.getVollText?pDocumentNr=870501&pCurrPk=80105

Meyer U, Jäggi A, Beutler G (2012) Monthly gravity field solutions based on GRACE observations generated with the celestial mechanics approach. Earth Planet Sci Lett 345–348:72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2012.06.026

Meyer U, Jäggi A, Beutler G, Bock H (2015) The impact of common versus separate estimation of orbit parameters on GRACE gravity field solutions. J Geod 89(7):685–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-015-0807-3

Meyer U, Jäggi A, Jean Y, Beutler G (2016) AIUB-RL02: an improved time series of monthly gravity fields from GRACE data. Geophys J Int 205:1196–1207. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggw081

Pavlis NK, Holmes SA, Kenyon SC, Factor JK (2012) The development and evaluation of the Earth Gravitational Model 2008 (EGM2008). J Geophys Res 117:B04406. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB008916

Pearlman MR, Degnan JJ, Bosworth JM (2002) The International laser ranging service. Adv Space Res 30(2):135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0274-1177(02)00277-6

Petit G, Luzum B (eds) (2010) IERS Conventions (2010). IERS Technical Note No. 36, Bundesamts für Kartographie und Geodäsie, Frankfurt am Main

Ramillien G, Lombard A, Cazenave A, Ivins E, Llubes M, Remy F, Biancale R (2006) Interannual variations of the mass balance of the Antarctica and Greenland ice sheets from GRACE. Global Planet Change 53(3):198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2006.06.003

Sakumura C, Bettadpur S, Bruinsma S (2014) Ensemble prediction and intercomparison analysis of GRACE time-variable gravity field models. Geophys Res Lett 41(5):1389–1397. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL058632

Sasgen I, Martinec Z, Fleming K (2007a) Wiener optimal combination and evaluation of the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) gravity fields over Antarctica. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 112:B04401. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004605

Sasgen I, Martinec Z, Fleminga K (2007b) Regional ice-mass changes and glacial-isostatic adjustment in Antarctica from GRACE. Earth Planet Sci Lett 264(3–f):391–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2007.09.029

Savitzky A, Golay MJE (1964) Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal Chem 36(8):1627–1639. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60214a047

Schlüter W, Behrend D (2007) The International VLBI service for geodesy and astrometry (IVS): current capabilities and future prospects. J Geod 81:379–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-006-0131-z

Seo KW, Wilson C, Waliser JCDE (2008) GRACE’s spatial aliasing error. Geophys J Int 172:41–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03611.x

Sneeuw N (1992) Representation coefficients and their use in satellite geodesy. Manuscr Geodaet 17:117–123

Steffen H, Petrovic S, Müller J, Schmidt R, Wunsch J, Barthelmes F, Kusche J (2009) Significance of secular trends of mass variations determined from GRACE solutions. J Geodyn 48(3–5):157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2009.09.029

Tapley BD, Bettadpur S, Watkins M, Reigber C (2004) The gravity recovery and climate experiment: mission overview and early results. Geophys Res Lett 31:L09607. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL019920

Teunissen PJG, Amiri-Simkooei AR (2008) Least-squares variance component estimation. J Geod 82(2):65–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-007-0157-x

Velicogna I, Wahr J (2013) Time-variable gravity observations of ice sheet mass balance: precision and limitations of the GRACE satellite data. Geophys Res Lett 40:3055–3063. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50527

Wahr J, Molenaar M, Bryan F (1998) Time variability of the Earth’s gravity field: Hydrological and oceanic effects and their possible detection using GRACE. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 103(B12):30205–30229. https://doi.org/10.1029/98JB02844

Watkins MM, Yuan DN (2012) JPL Level-2 Processing Standards Document For Level-2 Product Release 05. Tech. rep., NASA JPL, ftp://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/allData/grace/docs/L2-JPL_ProcStds_v5.1.pdf

Watkins MM, Gruber T, Bettadpur SV (2000) Science data system development plan. Tech. Rep. 327–710, GRACE Mission, ftp://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/allData/grace/docs/sds_dev_plan_c.pdf

Weigelt M, Sneeuw N, Schrama EJO, Visser PNAM (2013) An improved sampling rule for mapping geopotential functions of a planet from a near polar orbit. J Geod 87(2):127–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-012-0585-0

Wouters B, Bonin J, Chambers D, Riva R, Sasgen I, Wahr J (2014) GRACE, time-varying gravity, Earth system dynamics and climate change. Rep Prog Phys 77(11):116801. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/77/11/116801

Zhao Q, Guoa J, Hua Z, Shia C, Liua J, Caia H, Liud X (2011) GRACE gravity field modeling with an investigation on correlation between nuisance parameters and gravity field coefficients. Adv Space Res 47(10):1833–1850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2010.11.041

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Grant Agreement No. 637010. The authors are thankful to ITSG at the Graz University of Technology for providing their sensor fusion data. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers, the responsible editor of this manuscript, and the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Geodesy for the valuable advice to improve this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jean, Y., Meyer, U. & Jäggi, A. Combination of GRACE monthly gravity field solutions from different processing strategies. J Geod 92, 1313–1328 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1123-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1123-5